I prefer to see with closed eyes – In conversation with Josef Albers

2025 | Museum of Modern Art Gunma | Gunma, JP

Art: A way forward into the future-Jose Dávila’s conversation with Josef Albers

“Color, in my opinion, behaves like man-in two distinct ways: first in self-realization and then in realization of relationships with others…I’ve handled color as man should behave. With trained and sensitive eyes, you can recognize this double behavior of color. And from all of this, you may conclude that I consider ethics and esthetics as one.” -Josef Albers

Incorporating iconic works from the repertoire of art history into works of art in a recognizable way is a method developed and established itself as a vocabulary of expression, particularly in the course of 20th century art, from Surrealism to Pop Art. Quotation, allusion, and appropriation-they were homages, but at the same time, they seemed to be a sort of play between the creator and the viewer who could share knowledge of that iconic image, with the common understanding that the originality has always the highest value. In the 21st century, thanks to the Internet, everyone has access to a vast number of images from all times and places of the world. In the present age, where art history itself is shared as an open source, the question of what to create based on the legacy of predecessors is questioned more than ever.

Jose Dávila, who studied architecture at university in his hometown of Guadalajara, is part of a generation of artists who began working in the 1990s in a post-Cold War free market economy and a rapidly globalizing culture. His work spans a wide range of disciplines, including three-dimensional works, installations, paintings, and photographic cut-outs. He is best known for his installations with building materials such as glass and stone veneer panels held in place by cargo straps to maintain a precarious balance, and his three-dimensional works that combine the Acapulco chair, which originated in Mexico’s resort areas, with boulders and suspend them in mid-air. Among his most representative works are those inspired by 20th-century artists such as Pablo Picasso and Donald Judd, and Luis Barragán, one of the leading modernist architects of his native city. Josef Albers, a leading abstract artist, also captured Dávila’s heart, and this exhibition consists entirely of works based on Albers’ Homage to the Square series, which Dávila has been working on, off and on for more than a decade.

Homage to the Square – an icon of 20th century art

Josef Albers (1888-1976), who studied and taught at the Bauhaus, moved to the United States in 1933 when the institution was closed due to Nazi pressure. After developing his legendary art education at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, from 1950, he started Homage to the Square series, while he taught at Yale University and other institutions, spreading his theories.

The production of Homage to the Square series began when Albers was sixty-two and continued for more than 25 years until his last year, when he was eighty-eight. As is well known, the series experimented with the interaction of colors by arranging colored surfaces in the form of four or three nested squares, and it is said to have been executed a thousand or even over two thousand pieces in total. The paints were applied directly from tubes onto Masonite (hard fiberboard), mainly using a palette knife. The squares were not painted on top of each other, but each color was applied directly onto a white base. The four or three transparent colors, which are free from the murkiness caused by color mixing, change their appearance depending on the neighboring colors. The illusion also creates a sense of depth that is not there in reality, and one square may appear to be located on top of another square. With this work, Albers makes the viewer aware of the perceptual mechanisms and illusions involved in seeing colors. He also generously explained the theory embodied in his work through lectures, talks and writings. His book The Interaction of Color(first published in 1963), which begins with the introduction ‘In visual perception, a color is almost never seen as it really is’, is still the bible for those working with color today.

Homage to the Square, with its luminous colors and repetition of the square, the most fundamental of geometrical shapes, quickly captured the hearts and minds of the public. It became one of the cultural icons of its time, featured in Life and Vogue magazines and appearing in television programs and cartoons in The New Yorker magazine. Naturally, there have also been a number of artists who have produced their works based on Homage to the Square. Each has reinterpreted the work with their own interpretation, but it is rare to find an artist who has worked with this series repeatedly, in a variety of techniques, materials and scales, over as long a period as Dávila has. This article will consider the relationship between the two, explaining each work based on Homage to the Square by Dávila.

Early Works

In his essay, Dávila recalls the first time he saw Homage to the Square. In fact, it was a replica that hung on the wall of the Luis Barragán House in Mexico City (now a World Heritage Site and open to the public) when he visited. More than a decade after this encounter as a student, what can be seen as the starting point for a work based on Homage to the Square appears in Dávila ‘s early work at Art Basel Miami Beach in 2008, he painted a cargo container in blue and sliced it into a series of square arches of several dozen centimeter pieces, like cutting a rectangle cake. This object, which can also be seen as an influence of Barragan’s architecture, looks like a huge three-dimensional version of Homage to the Square when seen from the front. He produced a similar work in 2015 in a different color, as well as a similar motif in 2018 as a sculpture made with stainless steel in approximately the same size. These large works are named Untitled.

Ceramic tile work

In 2011, Dávila executed a work Untitled in which ceramic tiles, commonly used as building materials in kitchens and bathrooms, were cut into 20 to 50 cm pieces and layered in a composition similar to Homage to the Square. The following year, at Art Basel Miami Beach, he created an installation consisting of four huge grids of 8 meters square, laid out on the lawn in front of the Bass Museum of Art. The grids were stepped and lowered toward the center, creating a square where everyone could sit and relax. In his essay in this catalogue, Dávila describes this work as particularly memorable, leading him to the idea that “the work is complete when the viewer is inside (he describes it as ‘inhabiting’) the work.

The soft contours of the hand-cut tiles echo the fact that the contours of Albers’ Homage to the Square, while appearing to be mechanical shapes made with a ruler, are in fact drawn freehand, with the borders of the colored surfaces vibrating upon closer inspection. Furthermore, the colored tiles are reminiscent of Albers’ early work Stacking Table (c. 1927), which has colored glass tops that also hint at the juxtaposition of colors in Homage to the Square. method of using building materials and industrial products to give his works a simple appearance of reduced form resonates with Albers’ belief in ‘economy of means’, that is, achieving maximum effect with the minimum of materials and means by exploring the possibility of materials and techniques. resonates with Albers’ philosophy of ‘economy of means’. This is also what the artist describes in his essay.

Albers’s Homage to the Square is often discussed in terms of the three-dimensional illusions of depth that result from the color combinations used. The square that Dávila creates by layering tiles has a physical depth, resembling a stair pyramid seen from above.

Glass Works

Although not included in the exhibition, there are Homage to the Square based works using glass, Dávila’s preferred material in other installations. In these works, four pieces of colorless glass cut into squares are placed on top of each other on a colored wall that has been painted in the same shape. The color on the wall reaches the viewer’s eyes through the glass, and differences in the number of layers of glass are perceived as differences in color gradations. In contrast to Albers’ use of a combination of different paints, Dávila describes this work as a “painting by light” because it creates a device in which the color changes through the transmitted light of the layered glass. The method of revealing the relationship between light and color through the mere act of placing glasses up against the wall reminds us once again of Albers’ teaching on the “economy of means”. During his time at the Bauhaus, he took a strong interest in glass and incorporated it into his work. In this respect, we can find common elements in the work of both artists.

Homage to the Square mobile works

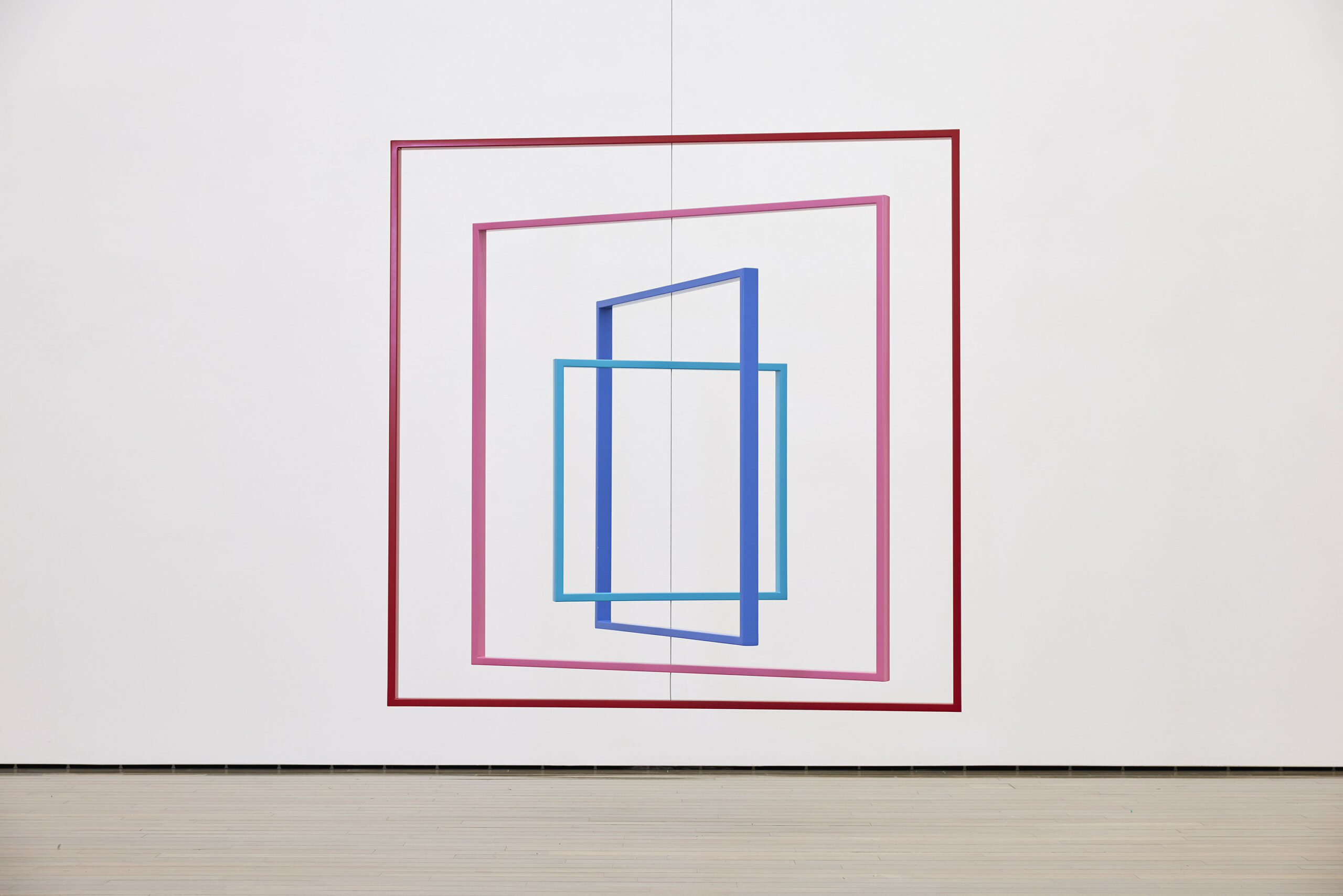

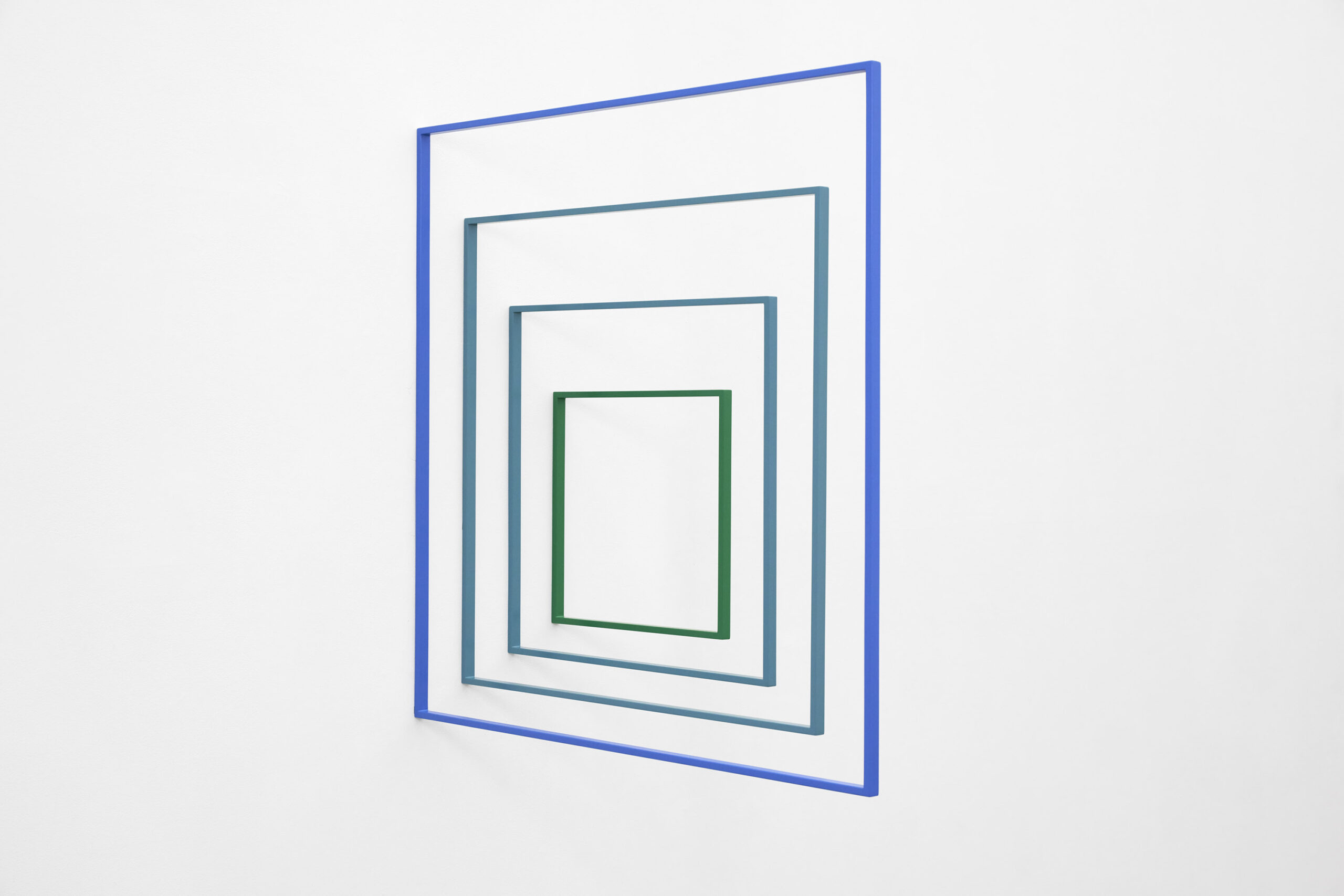

The mobile works, named Homage to the Square Dávila started around 2013, expresses the influence of Albers’ series more directly than the previous work entitled Untitled. The work consists of a series of square frames made with stainless steel that rotate on a wire axis and are nested together to form a skeletal reproduction of the composition of Albers’ work, albeit in varied sizes. The structure of the square frames, which are suspended, rotate, and change form, is a major feature of the work. Some mobiles are monochromatic, while others are painted in different colors for each frame, and the flight of ideas from Albers’ work, to make colors move, has led to new expressions. And, moreover, the slow movement of the mobiles is also noteworthy. The mobile, which was invented by Alexander Calder and is one of the inventions of 20th century abstract art, is characterized by its ability to change shape in response to the slightest movement of the air. The slow but ever-changing shapes of these works are at the borderline between the static and the dynamic. Around the same time in 2014, Dávila began showing Joint Effort series, also based on the theme of movement and stillness. This work, in which material objects are combined to resemble the poses of dancers standing still in impossible positions, evokes the dynamics of equilibrium that occurs to maintain that state. Dávila’s interest at the time in blurring the line between stillness and movement also gave new expression to his Homage to the Square series.

The Exhibition as a Work of Art

Dávila was an early member of OPA (Oficina para Proyectos de Arte), an independent space for artists established in Guadalajara in 2002 and has curated exhibitions for other artists. As such, he places great importance on creating a unique narrative for each of his solo exhibitions.

This time, to commemorate the fact that this is a two-person show, Dávila has used a bi-color mobile as the main image on posters and other materials, and he has also created new pieces for the series. And he chose the motifs of Homage to the Square from Albers’ print book Formation: Articulation and created tile works in the same color schemes used in prints. Visitors to the exhibition can see the playful interplay between Albers’ and Dávila ‘s works, which are displayed next to each other.

In this way, the exhibition layout itself becomes a new conversation with Albers and a summary of Dávila’s own Homage to the Square series. In his essay, Dávila refers to French novelist Georges Perec’s philosophical essay Species of Spaces, a quasi-treatise on the inhabitation, with which he discusses the space in Albers’ works and his own. In the exhibition, we can move freely between Dávila’s mobile works of many sizes, tile works, and Albers’ painting and prints, and experience, if only for a brief time, what he calls “inhabiting” work of art.

In his essay, Dávila reveals some of the secrets of his creation and speaks frankly about the relationship he established with Albers and with art history. His generosity may also reflect Albers method of education. The relationship he has established with his predecessors transcends time and space, and now he himself will pass it on to the next generation. This is parallel with what Albers meant when he has spoken of color and human behavior: “first in self-realization and then in realization of relationships with others”. We are fortunate to be able to experience this connection while placing ourselves in the exhibition space.

Seiko Sato (curator, The Museum of Modern Art, Gunma)